Interest on the National Debt—Who Does It Go To?

This week, to start off “Ask an Economist” for the year, I have a question from Stan K. about the national debt. I’m happy to report that after asking for questions in early January, I have received the most ever. I look forward to working through all I can. Here is Stan’s question:

Peter, I often bemoan the mess we have as our national debt climbs and interest on the debt becomes one of our biggest mandatory expenses. However, I was pontificating on this budget-busting danger to my wife, and she asked, “Who do we pay interest to, and how do we pay it?” My answer was pathetic. Can you help me out?

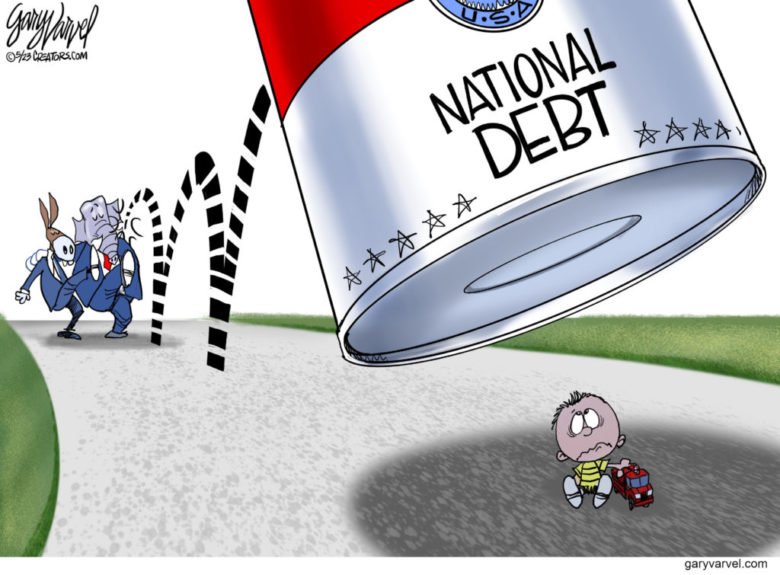

So we have a question about the ever-growing US debt. Let’s look at who owns it and how it’s paid.

How the Government Borrows Money

When the government borrows money, it does so in a different way from when you and your family borrow money. Most of the time when individuals borrow money, they take out a loan which accrues interest and is paid back monthly (or at some regular interval).

Not so with the government. Instead, the government takes on debt by issuing a bond. You’ve likely heard of government bonds before. Maybe you received one from a grandparent when you were a kid—meant to show you the value of waiting. Many people include bonds as part of their financial portfolios, especially as they get closer to retirement.

The government offers a few types of bonds that operate with some differences, but here’s how they generally work. You buy a bond which has a face value of, say, $1,000. After the bond matures (some bonds take as long as 30 years to mature) you receive the $1,000.

Why would anyone buy something that gives you $1,000 after waiting 30 years? Well, it must be the case that it costs less than $1,000 to purchase said bond.

This is the core of how government borrowing works. The government sells bonds to investors and groups and offers to pay them more than the cost of the bond in the future.

While interest doesn’t accrue on bonds in the fashion we’re used to, there still is “interest” in an important sense. Whenever you get money today in exchange for paying back more future money, you’re taking out a loan.

Bond interest is implied by the terms of the specific bond. For example, if you have a one-year bond which costs $1,000 and can be redeemed for $1,050 when it matures, the implied annual interest rate is 5% ($1,000*1+0.05).

Stan is right. As the government’s debt grows, the amount of money the government must pay on interest increases. If the government issues a single one-year bond redeemed for $1,050 as above, taxpayers have to pay $50 in interest. If the government issues two such bonds, it will end up being $100 in interest. If tax revenue can’t pay the bond, government officials will either have to increase taxes, take out a new bond increasing the debt and interest even further, or print money. All of these essentially amount to a tax increase.

The problem for future taxpayers doesn’t end here, though. As government tries to borrow more, it has to offer increasingly better deals in order to entice lenders. After a while, promising $1,050 on a $1,000 bond won’t convince any new lenders. The government will have to up the ante to $1,060.

Who Do We Owe Interest To?

Some experts like to claim that government debt and interest payments aren’t a big deal because we mostly “owe it to ourselves.” This is mostly wrong, but to see why, we first have to ask who owns government bonds.

The Peter G. Peterson Foundation has a good article on accounting for who owns the debt.

The article starts by pointing out that 22% of the national government’s debt is owned by the government itself. Government agencies often do this sort of thing for bookkeeping purposes, but it’s fair to say that to some extent this portion of the debt is simply money that the government owes to itself and is less important as a result.

What about the remaining 78%? Well, about one third of the remaining debt is held by foreign citizens and groups. In other words, around $7.3 trillion of bond payments are owed to foreign individual investors, groups, and governments. The largest two nationalities that hold US debt (outside of US citizens) are the Japanese and the Chinese.

The other nearly $20 trillion are owed to domestic groups.

When you hear people claim, “we owe the debt to ourselves,” this is often the debt they are talking about. It seems innocuous to some that the holders of US debt are US citizens. It’s an understandable mistake. After all, if we receive goods and services today and pay for them tomorrow, what’s the big deal? People take out loans all the time.

The problem with the “we owe it to ourselves” mindset is that it over-aggregates. To adapt a quote from Nobel prize-winning economist F.A. Hayek, this “aggregat[ion] conceal[s] the most fundamental mechanisms of change.”

What do I mean by this? Remember, government debt sometimes is held…